I’m not sure if it’s a strange thing to collect letters and postcards that make you feel sad. On the whole, most of what I collect makes me feel very happy so I can’t quite explain to you what my fascination is with letters and postcards sent from the front in World War I. The words of young men in these most horrendous conditions, seeing death all around them and never knowing when or if they would see their loved ones again are as beautifully touching as they are so awfully tragic. For me, there is a deep poignancy in their simple greetings and messages of love that are so much more powerful some hundred years later… These are the actual voices of men who were part of a long, brutal, world war which is recorded in all our history books, learned about at school and dramatised on screen.

I’m not sure if it’s a strange thing to collect letters and postcards that make you feel sad. On the whole, most of what I collect makes me feel very happy so I can’t quite explain to you what my fascination is with letters and postcards sent from the front in World War I. The words of young men in these most horrendous conditions, seeing death all around them and never knowing when or if they would see their loved ones again are as beautifully touching as they are so awfully tragic. For me, there is a deep poignancy in their simple greetings and messages of love that are so much more powerful some hundred years later… These are the actual voices of men who were part of a long, brutal, world war which is recorded in all our history books, learned about at school and dramatised on screen.

For the purpose of this blog post, I wanted to share with you three messages home sent during WWI. They are all sent from France and have all been stamped as passed by the censor. This is because all outbound communication had to be checked to ensure that it wasn’t giving away battle strategy and also that the content was purely positive in order to keep up the good morale back home, reiterating the message that the men were fighting a war that they fully intended to win.

Interestingly, war historians argue that letters and postcards home may not always give an accurate illustration of what life on the western front was actually like. They believe that the formal censorship – performed by an officer bestowed with the task of reading his comrades letters and postcards – and the ‘self censorship’ – the curtailing of candid correspondence by the soldier himself to avoid upsetting his loved ones – renders this communication as more of a sentimental nature than accurate.

From what I have researched, it appears that official censorship of communication was pretty crude. Many officers given the duties of censor felt uncomfortable reading their men’s letters and so an element of trust often came in to play as the officer stamped the soldier’s envelope. There was of course always the risk of getting caught however, and a letter home that was sad, hopeless and sick of war would have been considered a serious offence. While there is no doubt that many letters did fall foul to the official censors and never make it home, I suspect that the most powerful censors were the soldiers themselves. These men wanted to protect their families back home from the horrors of real war. Young men wished to conceal their fears from their mothers, husbands didn’t want their wives to worry, fathers wanted their children to believe that they would return victorious.

However, regardless of censorship, communication from soldiers on the western front is so rich in love and all that is wonderful and sacred about humanity. Perhaps it is this that makes these postcards and letters – while so painfully sad – so incredibly special to me.

Here are three very special – and very different – messages home from soldiers fighting in France during World War I. I feel honoured to hold their cards and letters in my hand some 100 years later.

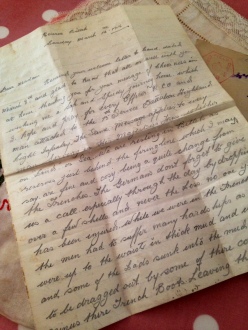

Letter from the trenches, 1916.

“Dear Madam,

Received your welcome letter to hand dated March 8th and glad to know that all is well with you at home. Thanking you for your message of cheeriness in wishing me a safe and speedy journey home which I hope and pray for every officer, n.c.o and man attached to the 15th Service Battalion Highland Light Infantry. The same message applies to every man serving in his majesty’s forces whether on land or sea. We are resting in billets as reserves just behind the firing line which I may say are fine and cosy being quite a change from the trenches. The Germans don’t forget to give us a call especially through the day by dropping over a few shells and never the less no one yet has been injured. While we were in the trenches the men had to suffer many hardships as they were up to the waist in thick mud and water and some of the lads sunk into the mud having to be dragged out by some of their comrades minus their trench boots. Leaving them behind as a souvenir. The Germans kept us lively by sending all their deadly weapons, our artillery replying back three shells to their one. Sad to relate, just the day before we left the trenches that afternoon about three o’clock the Germans sent over one of their whizz bangs, killing the man in charge of the water tank who was struck on the back of the neck by a piece of shrapnel. Poor fellow he suffered no pain. He died a hero. For the honour of God and of his country. He was loved by all and sadly missed. Also at the same time the two men who were filling their water bottles at the tank got slightly injured by shrapnel. Our boys are all looking well in health and strength ready for any duties they may have to perform. The weather today is lovely reminding you of a day in August. Beautiful sunshine, a change from the falling snow. Madam I will say no more concluding my letter in wishing you good health and happiness. As for myself I am enjoying good health and strength. I remain your in sincerity, William Giles”

I feel really privileged to own this letter. Although Private Giles goes to great lengths to illustrate his ‘high spirits’ and keep up morale, he does give us a real glimpse into life in the trenches. He talks of things that we have come to know from the history books and television, and yet reading his actual words, his soft pencil on lined paper, makes it so very human and real. His letter illustrates the fragile nature of life that Private William Giles would have gone on to see played out spectacularly – and tragically – in time.

William Giles has included the name of the battalion to which he belonged and this meant that I was able to search for his name in a list of WWI soldiers who were reported as killed/missing in action. I couldn’t find his name on that list, so I can only hopefully assume that Private William Giles eventually returned home to those who loved him.

Postcard from Dunkirk, 1917

“Thanks for Sunday’s letter dear, you are a busy little person – don’t over do the thing. I am writing tonight. No dear thanks I would not have any fruit out here. It would not travel besides we still get plum and apple jam!”

I wonder who the writer was writing to here? It’s a ‘Miss’ but is it his daughter, fiancée or sister? He talks to her in a childlike way – ‘you are a busy little person’ but it’s impossible to know exactly who was busying herself and wanting to send food parcels to J.V.A.D. One thing that really stands out here is the line about still getting plum and apple jam. This shocked me, as with all the food shortages, all the horrendous conditions endured by soldiers… did they really get to enjoy the home comforts of plum and apple jam? Perhaps – in keeping with the rest of the tone of the postcard – the writer didn’t want Miss Howell at home to worry about him. There is something very touching about this ‘upbeat’ postcard for that reason.

Finally, a postcard from France dated 1918. I have had this card a few years and when it first came to me I traced the PO stamp to the Somme region.

The card is from a father to his daughter. I can just imagine the father choosing this card with the cute illustration and the touching words ‘The time seems long without you’. On the back of the card, the soldier has simply written,

“Are these your sentiments? Father”

I can’t even begin to imagine what life was like for these men who hadn’t seen their children in so long and who must have wondered if they would ever see them again. There is so much said here in so few words. I sincerely hope that this soldier made it home to his daughter.

This is the strange thing about these cards and the letter. I know that so many soldiers did not return from the war (Britain lost almost a million men, most of them dying on the western front) and while I have no connection or link to the three soldiers who sent these messages, I desperately hope that they made it back to their loved ones. Somehow, in holding the bits of paper they held in their hands 100 years ago and tracing their soft, pencil written words with my finger, I feel something for these three soldiers. Their paper and their writing are as real and as present as anything else in my house today and yet those pieces of paper are still here and the men are not. Perhaps some words are meant to last forever, and by reading these words all these years later we are keeping the memory of these men alive.

Thank you for reading.